College of Human Sciences

Religious Studies: Past Wisdoms, Present Contestations, Future Trajectories

The Department of Religious Studies and Arabic in the College of Human Sciences hosted a symposium on Religious Studies: Past Wisdoms, Present Contestations, Future Trajectories in honour of its retiring staff member Professor Danie Goosen. Speakers included various members of the department as well as Professor Goosen’s loved ones and colleagues.

Contextualising the seminar, various scholars said that religious studies finds itself invigorated by various turns that have characterised the discipline through its history. In more recent history, for example, we have had the genealogical and material turns. As exciting as these are, the discipline is still animated by recurring debates that have been characteristic of the field since its inception. Past wisdoms co-exist with newer trajectories. And the discipline is best served by engaging both dimensions.

Professor Goosen, among others, has been keen to negotiate a trajectory for religious studies by drawing on the inherited legacies of the discipline while being deeply cognisant of present and future challenges. In the process he has revisited notions such as self, tradition, modernity and community in the light of a prevailing late capitalist reality. This symposium took into account this negotiation between past, present and future in religious studies as a whole and as developed in the thought of Professor Goosen in particular.

In his reflections, Professor Goosen presented on Thinking Thought Again, reflecting on what makes the intellectual pursuit possible, namely thought itself. He focused on what can be described as the “somewhat strange circular nature of thought”. He argued that the nature of thought is marked by an Odysseus-like journey back home. For analytical purposes, he identified four different phases in this “strange journey”.

“Following Plato, it can still be argued that the origins of philosophical thought can be traced back to the experience of wonder in the face of incomprehensible being. In the second phase, thought is invited to a conversation (or more pretentiously put, a dialogue) about the nature of wonder eliciting being. With the help of its many discursive instruments, rational thought asks, amongst other things, the so-called 'what is' question. In so doing, the mind attempts to set limits to being, thus hoping to make it understandable. However, discursive rationality (or what Plato named the rational part of the soul, dianoia), comes at a price. Although it may give us glimpses of wonderous being, its discursive nature causes us to stand at a distance from being itself,” he said.

Professor Goosen continued: “In the third and penultimate phase, therefore, thought reaches back to the initial state of wonder, but now with a difference. Instead of being overtaken by dumb perplexity as in the beginning, thought now steps ecstatically into the direct presence of wonderous being. The latter is reached using the intuitive part of the soul (or what Plato describes, after the concept noesis, as the noetic part of the soul). In and through noesis thought enters in a sunousia – a coming together, a nuptial unity of consciousness and wondrous being. Strangely enough, this is not where the journey ends.”

He added that in a fourth and last phase, thought steps even beyond the intuitive unity with being into the presence of what can be described, rather enigmatically, as the ‘open’. “According to ancient thought, the latter represents a sphere beyond being. As the first principle of being, openness is the ‘spaceless space’ that enables being to be disclosed at all. Traditional thought referred to it as the Good, the One, the Whole, the All, Being or God. Instead of approaching the open with the rather noisy ‘to and fro’ of discursive reasoning, or even the ecstasy of intuitive insight, it is approached in ‘liturgical silence’.”

Professor Goosen then spoke on some aspects of what has been described as thoughts’ four-step dance where he looked at the experience of wonder, the dialogue between question and answer, and then thought and silence.

He tied this all in with remarks on his retirement. “Indeed, as we argued, the dialogues start and end in wonder. For in the overwhelming light that is the good we are again struck by wonder, as at the beginning of thought’s journey.

“Nevertheless, there is also a difference. At the end of the journey, we are still ignorant. But unlike the initial wonder, we are not caught in perplexed ignorance. No, our ignorance is deepened. We can even describe it as a holy ignorance. This ignorance does not stem from the feeling that everything is dark, opaque, resistant to light. To the contrary, holy ignorance stems from being overwhelmed by an abundance of light made possible by gift-giving openness.”

He said the mere attempt to say the gift-giving openness and the fullness it represents is a sure guarantee that we will lose it. For speech inevitably reduces the gift-giving openness to the order of being. If it can be approached it at all, it is not through highfaluting theory or embroidered language, but through a simple practice – the practice or liturgy of silence. Nothing but complete silence.

“However, before we enter the sphere of silence, allow me to express my deepest thanks and appreciation. Gift-giving openness has given me (without reserve or the expectancy of a return) a life enriched beyond words by a loving family, wonderful friends, fearsome enemies, and colleagues to be treasured long after I have left the corridors of Unisa,” he concluded.

Click here to read Professor Goosen’s reflections.

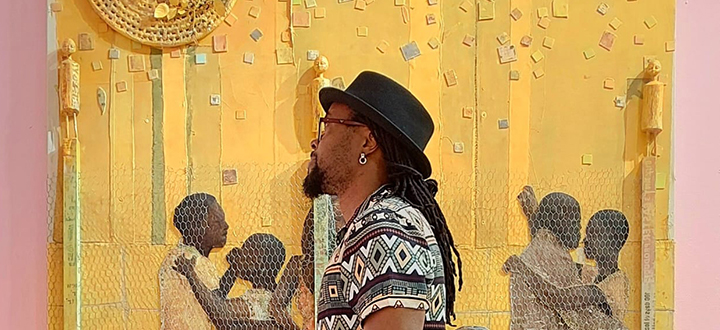

Pictured are staff members, colleagues and loved ones of retiring professor from the Department of religious Studies and Arabic, Danie Goosen (back row, centre).

* Compiled by Rivonia Naidu-Hoffmeester

Publish date: 2018/11/09

New Unisa partnership set to benefit youth and unemployed graduates

New Unisa partnership set to benefit youth and unemployed graduates

Passion for music and the arts leads to the highest academic honour

Passion for music and the arts leads to the highest academic honour

Landmark exhibition reflects Unisa's Pan-African vision

Landmark exhibition reflects Unisa's Pan-African vision

Unisa paves the way for agricultural resilience and sustainability in the Eastern Cape

Unisa paves the way for agricultural resilience and sustainability in the Eastern Cape

Unisa empowers communities through school literacy project

Unisa empowers communities through school literacy project