College of Human Sciences

Towards a unified approach to language preservation and accessibility

Unisa recently hosted a transformative event under the theme "Preserving Languages: Open, Free and Accessible Knowledge for All", which brought together experts to advance the use of South African languages through innovative collaborations.

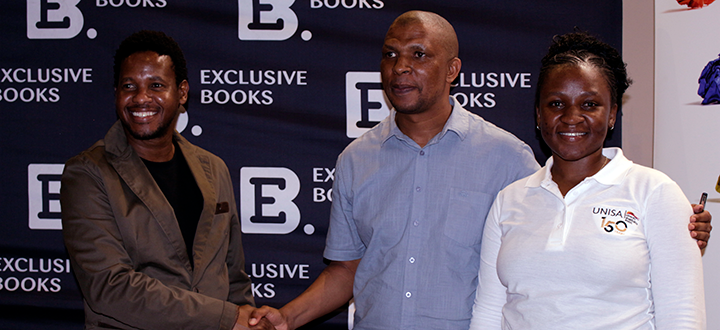

Participants from Wikipedia and the Department of African Languages

The event took place on 9 and 10 May 2024 at the Function Hall, Kgorong Building, University of South Africa (Unisa). This significant gathering was a collaborative effort between Unisa's Department of African Languages in the College of Human Sciences, the South African Centre for Digital Language Resources (SADiLaR), Wikipedia, and the Pan South African Language Board (PanSALB) under the SADiLaR-Wikipedia-PanSALB (SWiP) initiative. The SWiP project, officially launched on 20 September 2023 at Unisa, aims to enhance the use of South African languages by integrating various sectors involved in language practice.

The collaboration between SADiLaR, Wikipedia and PanSALB signifies a unified approach to language preservation and accessibility. The project seeks to engage university language directorates, language entities and communities of practice to contribute actively to the digital representation of South African languages. This initiative is particularly crucial as it aligns with the mission to make indigenous languages accessible on global platforms like Wikipedia.

During the event, I had the opportunity to interview Prof Stanley Madonsela, the Chair of the Department of African Languages at Unisa. Madonsela emphasised the multifaceted objectives of this collaboration. He highlighted that the Department of African Languages plays a pivotal role in this initiative, given its comprehensive offerings of all nine indigenous South African languages recognised by the Constitution. Through this initiative, departmental staff members are empowered to contribute to making these languages accessible to Wikipedia users, thereby fostering the preservation and promotion of linguistic diversity.

Prof Stanley Madonsela, Chair of the Department of African Languages

Madonsela elaborated on the significance of the collaboration, stating, "This initiative brings together different sectors with a common goal of making a meaningful contribution to providing data on Wikipedia platforms. It unites legislative, linguistic, digital, and academic resources to advance the use of South African languages". He noted that the initiative allows language communities of practice to participate actively in enriching Wikipedia's content, thereby leveraging available resources to promote linguistic diversity.

Discussing the broader impact of Wikipedia and SWiP on the general populace, Madonsela pointed out that Wikipedia serves as a crucial platform for everyday information access. "SWiP ensures that data on various topics is available to users in their respective languages, empowering them with knowledge that is relevant and accessible," he remarked. This initiative not only broadens the availability of information but also enhances the inclusivity of knowledge dissemination. Madonsela stressed that the preservation of indigenous languages is of paramount importance. "Our indigenous languages are integral to our cultural identity, carrying traditional knowledge, expressions of art, and invaluable wisdom. Preserving these languages is essential for maintaining our cultural heritage and ensuring the transmission of our customs and traditions," he asserted. Furthermore, documenting history in native languages is crucial for cultural continuity. "In an era where information dissemination is pivotal, documenting our history in indigenous languages ensures that future generations can access and understand their cultural heritage," Professor Madonsela explained. This process is vital for the preservation and transmission of culture, customs, and traditional heritage.

In conclusion, the "Preserving Languages: Open, Free and Accessible Knowledge for All" event underscored the importance of collaborative efforts in promoting and preserving South African languages. By integrating various sectors and leveraging digital platforms like Wikipedia, this initiative aims to make a significant impact on the accessibility and preservation of linguistic diversity in South Africa.

* By IHlubi Veli Mabona, Marketing Assistant, College of Human Sciences

Publish date: 2024/06/10

Unisa co-hosts G20 community outreach in the Eastern Cape

Unisa co-hosts G20 community outreach in the Eastern Cape

Unisans gain membership of prestigious science academies

Unisans gain membership of prestigious science academies

Advocating for disability transformation through servant leadership

Advocating for disability transformation through servant leadership

Unisa Press continues to illuminate the publishing space

Unisa Press continues to illuminate the publishing space