College of Agriculture & Environmental Sciences

Oil refinery blast is one more reason SA should take industrial risks seriously

Firefighters dousing the fire at the Engen oil refinery in Durban, South Africa, in December 2020. GettyImages

A blast at an Engen oil refinery recently rocked the community of Durban South, an industrial basin in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Several employees and community members were treated for smoke inhalation. The Conversation’s Nontobeko Mtshali asked Llewellyn Leonard to share his insights on South African communities and environments exposed to industrial risks.

The recent explosion at the Durban oil refinery is one in a long list of pollution incidents in the area. What has the government done to protect residents of communities surrounding the refinery?

The local South Durban Community Environmental Alliance recorded a total of 55 major industrial incidents in South Durban from 2000 to 2016. In 2018, the South Durban basin was declared a pollution hotspot, according to the provincial government’s Environment Outlook Report.

Although there were previous attempts by the municipality to implement measures to monitor and address pollution risks in South Durban under the previous Multi-Point Plan, the plan fell away in 2010. The plan was initiated by civil society and was a collaboration between the government, industry, and civil society. It resulted in an improved air quality monitoring network. The efforts have since collapsed because new local government leadership didn’t take the plan forward. This led to a complete collapse of air quality monitoring systems.

Due to poor governance, air-monitoring equipment hasn’t been maintained, industrial risks in South Durban haven’t been addressed, and the government hasn’t shared air quality information. The actual status of air quality in the area is unknown. Residents and civil society can’t make informed decisions about industrial development issues. This has implications for participation and transparency. Thus, monitoring, enforcement, and compliance have been weak.

Should a petrochemicals facility be in the middle of a residential area? What’s the experience like elsewhere in the world?

Definitely not. It’s always in the interest of people for industries not to be located in a residential neighbourhood, as we see in places like St James in Louisiana, in the US. The risk of air pollution and industrial accidents cannot be ignored, especially when such industries aren’t regulated or well managed or don’t abide by the law.

In some parts of the world governments have managed to locate heavy industries away from residential neighbourhoods. A case in point is Jurong Island in Singapore, which is an amalgamation of seven offshore isles. It was formed in 2009 and is home to over 100 industries, including ExxonMobil and Shell.

The locations of some hazardous industrial sites were informed by apartheid policies. Many of these industries are still operational. What are the implications and what should the government be doing about it?

The geographic setting of communities that were exposed to industrial risks during apartheid hasn’t transformed since democracy. During apartheid, the South Durban Basin became home to two of South Africa’s four oil refineries and Africa’s foremost chemical storage facility. Currently, it’s home to over 600 industries. It’s still an industrial hub that includes residential areas.

Due to the ageing infrastructure of operations such as Engen, the government should’ve long decommissioned such industries. They’ve always been a high risk for residents living next to them. Civil society, particularly the South Durban Community Environmental Alliance and groundWork, has been calling on the government to decommission dangerous industrial operations and move them away from residential areas. This hasn’t happened. Industries operate knowing enforcement of regulations has been limited. They have used the Regulation of Gatherings Act to ban residents protesting outside the facility.

A blast at an Engen oil refinery recently rocked the community of Durban South, an industrial basin in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Several employees and community members were treated for smoke inhalation. The Conversation’s Nontobeko Mtshali asked Llewellyn Leonard to share his insights on South African communities and environments exposed to industrial risks.

The recent explosion at the Durban oil refinery is one in a long list of pollution incidents in the area. What has the government done to protect residents of communities surrounding the refinery?

The local South Durban Community Environmental Alliance recorded a total of 55 major industrial incidents in South Durban from 2000 to 2016. In 2018, the South Durban basin was declared a pollution hotspot, according to the provincial government’s Environment Outlook Report.

Although there were previous attempts by the municipality to implement measures to monitor and address pollution risks in South Durban under the previous Multi-Point Plan, the plan fell away in 2010. The plan was initiated by civil society and was a collaboration between the government, industry, and civil society. It resulted in an improved air quality monitoring network. The efforts have since collapsed because new local government leadership didn’t take the plan forward. This led to a complete collapse of air quality monitoring systems.

Due to poor governance, air-monitoring equipment hasn’t been maintained, industrial risks in South Durban haven’t been addressed, and the government hasn’t shared air quality information. The actual status of air quality in the area is unknown. Residents and civil society can’t make informed decisions about industrial development issues. This has implications for participation and transparency. Thus, monitoring, enforcement, and compliance have been weak.

Should a petrochemicals facility be in the middle of a residential area? What’s the experience like elsewhere in the world?

Definitely not. It’s always in the interest of people for industries not to be located in a residential neighbourhood, as we see in places like St James in Louisiana, in the US. The risk of air pollution and industrial accidents cannot be ignored, especially when such industries aren’t regulated or well managed or don’t abide by the law.

In some parts of the world governments have managed to locate heavy industries away from residential neighbourhoods. A case in point is Jurong Island in Singapore, which is an amalgamation of seven offshore isles. It was formed in 2009 and is home to over 100 industries, including ExxonMobil and Shell.

The locations of some hazardous industrial sites were informed by apartheid policies. Many of these industries are still operational. What are the implications and what should the government be doing about it?

The geographic setting of communities that were exposed to industrial risks during apartheid hasn’t transformed since democracy. During apartheid, the South Durban Basin became home to two of South Africa’s four oil refineries and Africa’s foremost chemical storage facility. Currently, it’s home to over 600 industries. It’s still an industrial hub that includes residential areas.

Due to the ageing infrastructure of operations such as Engen, the government should’ve long decommissioned such industries. They’ve always been a high risk for residents living next to them. Civil society, particularly the South Durban Community Environmental Alliance and groundWork, has been calling on the government to decommission dangerous industrial operations and move them away from residential areas. This hasn’t happened. Industries operate knowing enforcement of regulations has been limited. They have used the Regulation of Gatherings Act to ban residents protesting outside the facility.

Residents gathered after the explosion at the Engen oil refinery south of Durban. GettyImages

The result of inaction by government has been increased health risks for South Durban communities. Asthma rates are among the highest in the world. The incidence of leukaemia has reported as up to 24 times higher than the national average.

As far back as 2002, a study by medical researchers at the local Settlers Primary School bordering the Engen refinery, found that 52% of learners suffered from severe asthma. It was also found that children in the region were much more likely to suffer from chest complaints than children in other parts of Durban.

Clearly government needs to monitor and enforce laws and regulations for existing industries and implement pollution reduction plans. No industrial expansion must be allowed that would increase pollution levels in South Durban. Government needs to work with industry to set up a 24-hour asthma and cancer clinic in south Durban, as residents called for over four years ago.

Are there best practices South Africa can draw from to strike a balance between economic development and the well-being of communities and the environment?

If South Africa continues with business as usual, with high intensive and polluting industries, including weak governance and enforcement, we’ll continue to see environmental incidents, dangerous levels of air pollution and resultant health impacts. The result will be continued protests by civil society against government, polluting and reckless industries.

The country needs to move away from a reliance on dirty industries, particularly fossil fuels. This will require introducing renewable energy industries that are clean, efficient, and safer for people and the environment.

In the United States, the renewable sector employs more than 3 million people. South Africa can increase employment opportunities by growing the share of renewable industries.

People must be trained and employed to establish the renewable sector and service it throughout the value chain—wholesaling, installation, maintenance, distribution, manufacturing, operations and research. Some of the top renewable energy employment countries are China, Brazil, the United States, Japan, Germany and India. South Africa must learn from others and seize the opportunity to move to clean industry.

*By Llewellyn Leonard, Professor Environmental Science, University of South Africa

Publish date: 2020/12/14

Unisa co-hosts G20 community outreach in the Eastern Cape

Unisa co-hosts G20 community outreach in the Eastern Cape

Unisans gain membership of prestigious science academies

Unisans gain membership of prestigious science academies

Advocating for disability transformation through servant leadership

Advocating for disability transformation through servant leadership

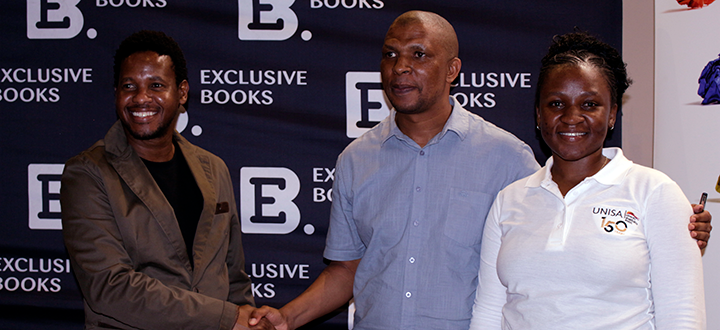

Unisa Press continues to illuminate the publishing space

Unisa Press continues to illuminate the publishing space