Equipped with state-of-the-art laboratories that provide students with hands-on experiences to bridge theory and practice

Prof Ashley Gunter, from the Department of Geography in the College of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences, delivered his inaugural lecture entitled "The geography of knowledge: Networks, nodes and mobility" on 30 June 2021.

In his introduction, Gunter said that to many people the spaces of education are very important. "The first time we were aware of these educational spaces was when we started school," he said. "We came to realise how these spaces made us feel. They were spaces that inspired us to learn, and formed a great part of our sense of geography."

Continuing with this line of thought, Gunter said that there are different nodes around the world. "These spaces attract people, knowledge, staff and books. The great institutions of the world, like Harvard and Oxford, create knowledge and attract students. Nodes have developed throughout history as spaces of knowledge and South Africa is certainly one of those. One of my research interests are the nature of nodes in Africa."

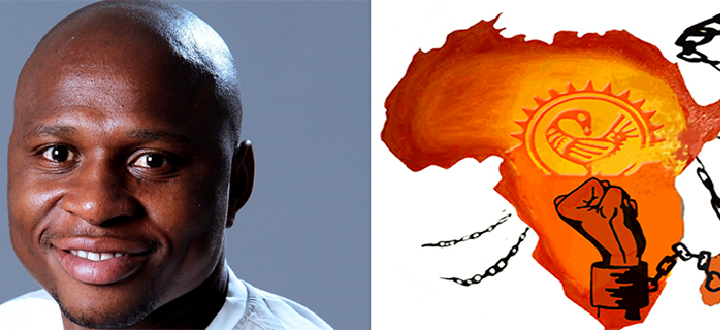

Prof Ashley Gunter

Gunter said that in Africa nodes are often linked to the branch campus movement, where institutions in the Global North have opened campuses and nodes in the Global South. "South Africa has been part of this," he said. "The country has been attracting students from beyond its borders, and particularly from SADC countries. We have always known that most African students prefer to study in the north, but increasingly African students are coming to South Africa. It shows that South Africa has this long history post-apartheid of attracting people as a node of education."

"There are different nodes that are linked to one another," said Gunter. "These nodes have strengths and weaknesses, and interact in different ways. There is a multiplicity of networks that form distance education, particularly in the context of Unisa. We have knowledge moving across the world and then we move into distance learning as another way of understanding the geographies of knowledge."

Gunter said that distance education, particularly, unbundles space and time. "No longer are you bound to a specific space to acquire a degree nor are you bound to a specific time for attending lectures," he explained. "Things have become far more fluid. The university stops becoming physical premises and starts becoming a network entity that is not about the classroom but is about imparting education around the world. The university becomes both everywhere and nowhere."

"Your network determines how well you can connect to the space of the university," said Gunter. "The educational experience becomes entangled with material objects (the cellphone, computer, internet) and having a study space (featuring things such as furniture and lighting). All of these form part of the network in which students engage with distance learning. There is a shift to understanding how students engage with university, and this is dictated by things not controlled by the university. Examples include electricity supply and internet connectivity. Even the university learning centres themselves can be unreliable, and so students do not necessarily have easy access to the system we call distance education. If a student’s internet access or electricity supply is not good, then that student will have a poor educational experience, and this can actually change the way she or he views the institution. The institution itself has very little control over this situation."

Gunter said that the Covid-19 pandemic has fundamentally changed universities. "The pandemic is pushing more and more people into the online study space, and universities are offering more online education," he said. "We must really understand how students are engaging with the institutions. This is no longer about going to an institution and being inspired by the architecture. Students now focus on the networks offered by institutions."

In conclusion, Gunter said that the main legacy he would like to leave in academia are the students and mentees that he had influenced in his career. "This includes helping students develop as researchers and inspiring early career academics to fulfil their potential," he said. "If I can have some future academics say they got to where they are because I helped them get there, I would feel that I have left a legacy I can be proud of."

* By Gugulethu Ncgobo, Communications Specialist, College of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences

Publish date: 2021/07/01

Unisa celebrates a project of hope, dignity and student success

Unisa celebrates a project of hope, dignity and student success

Women vocalists take top honours at Unisa's globally renowned showcase

Women vocalists take top honours at Unisa's globally renowned showcase

African wealth is dependent on investment in education and development

African wealth is dependent on investment in education and development

Unisa celebrates matric result success at Correctional Services ceremony

Unisa celebrates matric result success at Correctional Services ceremony

Unisa ICT Director recognised among acclaimed IT leaders

Unisa ICT Director recognised among acclaimed IT leaders