College of Economic & Management Sciences

International finance and ubungoma

These are exhilarating times for Makoni, a senior lecturer at the Department of Finance, Risk Management and Banking in the College of Economic and Management Sciences.

On the one hand, her work as an academic in the field of international finance and investment has seldom been more fascinating given the recent shifts in South Africa’s currency and investment status.

“Oh wow, this is my cup of tea—I wrote about this kind of stuff in my thesis; it’s really exciting,” says Makoni, who in December 2016 graduated from Wits University with her PhD on foreign direct investment and foreign portfolio investment and the role of financial market development in selected African countries.

On the other hand, her initiation as a sangoma a few weeks before her PhD graduation has brought her peace. Since accepting the call of her ancestors, after years of resisting, she has not again experienced the excruciating migraines that had been plaguing her.

“Ubungoma is not a choice; it’s a calling,” says Makoni, who only two years ago never imagined she would become a traditional healer: “…sitting on reed mats, throwing bones, diagnosing African-related conditions…not in a million years!”

Never say never

Makoni grew up in Zimbabwe in a staunch Roman Catholic family, where consulting a traditional healer was not done, especially for the children of a Western-trained medical doctor.

She completed her MSc in Finance and Investment at the National University of Science and Technology in Bulawayo and, not long afterwards, was seriously injured in a car accident. “I was told I would be in a wheelchair for life but the fighter in me emerged as I learnt the basics of walking and writing again.”

On making a full recovery, Makoni moved to Johannesburg as an investment consultant. “Although the position paid exceptionally well, I felt I was an academic at heart; as the old adage goes, once an academic, always an academic.”

She moved to the University of the Western Cape and then made her way to Unisa in 2010. “Life seemed to be going well. I was actively involved in the communities around me as a Zumba instructor, netball coach and umpire, as well as with Nehawu as the convenor of the academic desk at Unisa.”

Then the migraines started, often accompanied by voices and visions.

Wake-up call

A full night’s sleep became virtually impossible and Makoni would sometimes black out while driving. Then one day in October 2013, she passed out at work and was rushed to hospital, undergoing test after test—with no results. “The doctors could find nothing wrong.”

The migraines continued but she assumed she was simply overworking as she was balancing a full-time lecturing job with part-time PhD studies at Wits.

That situation changed for the better when she was accepted for Unisa’s Academic Qualifications Improvement Programme (AQIP), giving her three years off from work from January 2014 to complete her doctorate.

Still the migraines persisted.

Then in mid-2015, she accompanied a close friend to his appointment with a sangoma—whose face Makoni recognised from her dreams.

“The sangoma and one of her children instantaneously complained of a splitting headache. The sangoma said, ‘It’s you. Your ancestors have been calling you but you have not been paying attention. They are giving you all these illnesses so that you can learn how to heal yourself, and in the process learn to heal others.’”

Makoni resisted. “I got very upset and said, ‘This is insane, we don’t do these things in my family.’ The sangoma retorted that I was not open to my ‘gift’ because I thought I was ‘too educated’, and for that reason, I’d be sick until I answered my calling.”

Six months later, after fruitlessly trying alternative Western and Chinese medical interventions for the migraines, she surrendered. “The mere verbal acknowledgement of my ancestral gift marked the end of years of being a migraine-sufferer. I have never had them again since then.”

In January 2016 Makoni underwent a week-long pre-initiation process in preparation for her sangoma training (ukuthwasa), which could take three months or three years, depending on her ancestors’ wishes.

Tough choices: Unisa or traditional healing?

But there was a problem. “It was my last year on the AQIP programme and I was contractually bound to finish my doctorate,” Makoni says. “My Gobela (trainer) said I had to undergo my initiation full time, but we would ‘negotiate’ with my ancestors so that I could also complete my PhD, and in the process not lose my (Unisa) job.”

Her ancestors consented and Makoni started attending initiation school.

“A typical day would begin with waking up at 2.30am, and taking a cold bath outside, even in winter. From 3am, I would go into induma, ‘invoke’ my ancestors and spend an hour communicating with them. At 4am, it would be time for cleansing with different traditional herbal concoctions. Some patients would also come early in the morning for their treatments. I would do various household chores for uGobela and her family, before leaving for work.”

She usually arrived at the office around 6am. “I would work on my PhD through the day, then leave the office at 6pm and head back to initiation school. Sometimes I’d have to consult with patients in the evenings. If I slept before 11pm, I was very lucky.”

In August 2016, she submitted her PhD. Then, with her preparations for final PhD submission, she ran into a crisis.

“My thesis was assessed by three examiners but by 18 November 2016, I had received feedback from only two of them. When the third examiner’s comments finally came through, I had only one week before graduation to incorporate the changes and submit the final PhD draft.”

Back at work—but not business as usual

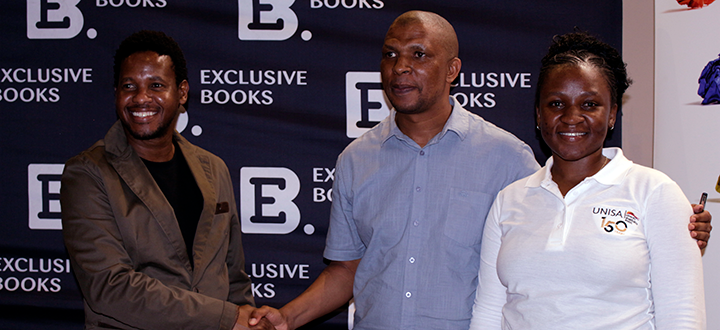

Having completed her sangoma initiation and her PhD at the age of 35, Makoni is back at work. In March 2017, she received the 2016 award for Youngest Female PhD Graduate at Unisa’s annual Research & Innovation Awards, and was also promoted from lecturer to senior lecturer.

Her calling as Sangoma will never be forgotten or sidelined, she vows.

In the evenings after work and on weekends, she and her life and spiritual partner work together at their healing practice in Hammanskraal. During her working day at Unisa, Makoni does her best to balance her position as an academic with her calling as a traditional healer.

“Every day brings its challenges. In order to ensure that my ancestors don’t feel neglected during normal working hours, I have to ask for their permission,” says Makoni, who maintains the connection with her ancestors by burning impepho (wild sage). Occasionally when she interacts with people, her body picks up on their different ailments, and she must hence inhale snuff to ward off the effects.

“Who said that you can’t be a sangoma in the professional space? Of course, I don’t expect everyone to understand the ‘new me’, but with the transformation agenda of the institution, I hope that colleagues will accept that ubungoma is not a choice; it’s a calling. So here I am, engaging our indigenous knowledge systems and helping people to find meaning in other spheres of their lives too, while simultaneously establishing myself as a young academic in the niche research field of international finance.”

May she succeed, and may her ancestral Nguni warriors and Ndau water spirits be proud.

*By Clairwyn van der Merwe

Publish date: 2017/06/21

Unisa co-hosts G20 community outreach in the Eastern Cape

Unisa co-hosts G20 community outreach in the Eastern Cape

Unisans gain membership of prestigious science academies

Unisans gain membership of prestigious science academies

Advocating for disability transformation through servant leadership

Advocating for disability transformation through servant leadership

Unisa Press continues to illuminate the publishing space

Unisa Press continues to illuminate the publishing space